Abstract

The Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV), and its subsequent disease progression Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome (AIDS), have presented significant and unprecedented challenges to the insurance industry. These conditions led to concerns of mounting and unfunded liabilities and essentially changed the way that insurance was underwritten.

Fortunately, with the development of new therapies, individuals with HIV are living much longer lives and the dire predictions for excess mortality losses for insurers did not materialize. For decades, individuals with HIV were considered uninsurable; however, a paradigm shift has recently occurred in the way insurers view HIV, based upon a growing body of evidence demonstrating improving mortality outcomes for infected individuals.

HIV is now transitioning to an insurable condition, but despite treatment success, it remains a complex disease, and designing insurance products with the right inclusion and exclusion criteria is a challenging task. Insurance medical directors and underwriting manual developers will need to follow medical literature closely and amend their guidelines as needed. This article discusses the main risk factors requiring assessment when coverage for individuals with HIV is being considered.

Introduction

HIV has resulted in millions of deaths globally since first reported in 1981. Today, according to the World Health Organization (WHO), 37 million people around the world were living with a diagnosis of HIV at the end of 2014, 25.8 million of whom were located in sub-Saharan Africa (which is also where 70% of all new infections occur)1.

With the advent of anti-retroviral therapy (ART) in the mid-1990s, HIV has become a controllable (albeit still chronic) disease. Life expectancies for the HIV-infected, once measured in months or even weeks, are now in the decades for those receiving ART. Indeed, annual death rates for newly infected HIV patients on ART currently approach those of the general population in short-term follow up. In the longer term, epidemiological studies have reported mortality ratios for those with HIV approaching those observed in individuals with other insurable chronic diseases. Morbidity risk for these individuals, however, continues and is yet to be quantified2.

As ART is increasingly allowing those living with HIV to remain active members of society – that is, to continue to work, run businesses, have families and purchase homes – they are needing life insurance cover to protect themselves, their families, and their businesses.

More than 10 years ago, insurers in South Africa and Europe began offering life cover to treated HIV-infected individuals on a limited-term basis. More recently, life insurers in the U.S. and Canada have also begun to develop and offer products to cover HIV-positive individuals.

Depending on inclusion and exclusion criteria selected as defining the better risk, offers can be made on a reasonable percentage of HIV positive applicants. Underwriting ratings can be determined by extrapolating data from various medical studies to ensure the additional premium assessed is fair. Due to the relatively high ratings for many of these applicants and the typical limited-term duration of these products, the placement ratio has been low, but is increasing.

Of note, in some countries durations of policies available to HIV-positive individuals have been extended to renewable term and whole of life products. Still, with low numbers of inforce policies covering HIV-positive insured people, credible claims experience is yet to be determined. This data will need to be followed carefully.

Life Expectancy/Mortality

Deaths from HIV have decreased dramatically over the past two-plus decades. Recent articles reviewing research on HIV mortality outcomes show that people are living longer and the majority of deaths occurring among those on treatment are now no longer due to AIDS defining illnesses3, 4. These articles, along with the following three studies, can serve as excellent reviews for anyone researching HIV mortality outcomes in the course of developing underwriting guidelines.

The Antiretroviral Therapy Cohort Collaboration (ART-CC) found that between 1996 and 2005, estimated life expectancy at age 20 had increased from 36.1 years to 49.4 years, and the number of those who survived from age 20 to age 44 increased to 85.7% by 20055. The UK Collaborative HIV Cohort (UK CHIC) study of patients (excluding injection drug users) infected with HIV-1 (the most prevalent form of the virus) who started ART in 2000-08 found that on commencement of treatment, estimated life expectancies for these individuals at age 35 were6:

.png?sfvrsn=ab44a388_0)

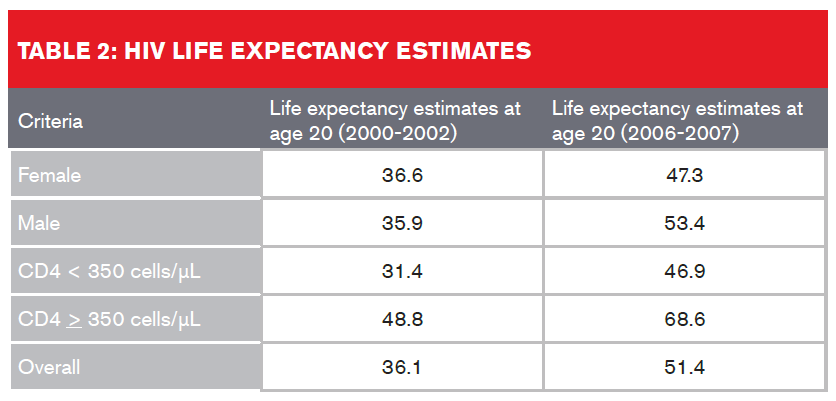

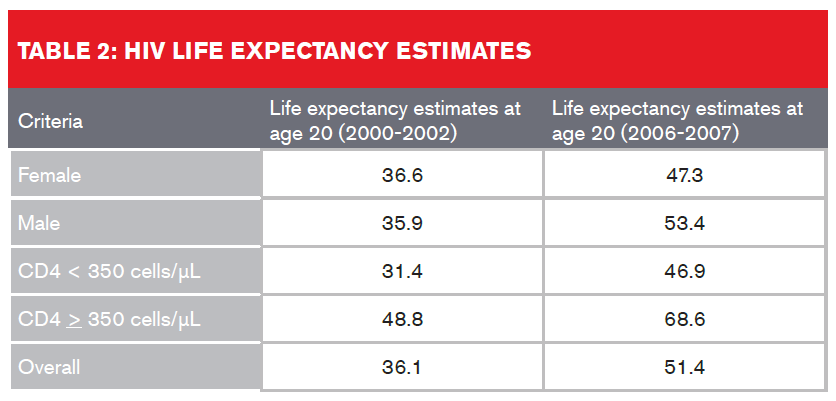

A study which looked at U.S. and Canadian participants in the North American AIDS Cohort Collaboration on Research and Design (NA-ACCORD) on ART between January 2000 and December 2007 found that overall life expectancy estimates increased from 36.1 to 51.4 years from 2000-2002 to 2006-20077. Table 2 (below) provides a breakdown:

Despite improved life expectancies, HIV-infected individuals still experience a higher rate of non-AIDS-related deaths than the general population. This discrepancy in life expectancies could be attributed either to the active HIV infection or to other underlying factors such as higher rates of alcohol use and smoking, co-infection of hepatitis C, or as a result of cardiovascular, cancer or liver disease. The presence of these comorbidities also needs to be assessed by insurers, regardless of undetectable viral load or high CD4 cell counts.

Comorbidities

Increased T-cell turnover in HIV infection causes increased generalized inflammation and endothelial damage. As a result, HIV-infected individuals are at greater risk of developing age-related diseases earlier than the general population.

The most frequently reported cardiac disease manifestations in HIV patients are

cardiomyopathy, pulmonary hypertension and pericardial disease. Increased cardiovascular risk may be due to inflammatory lipid alteration, indicated by a higher carotid intimal-media thickness (IMT) in HIV patients8. Older retroviral medications such as zidovudine (Retrovir) and stavudine (Zerit) are also more likely to cause dyslipidemia.

The Veterans Aging Cohort Study (VACS), conducted in the U.S. from 2003-2009, found that male HIV patients were at a 50% increased risk of myocardial infarction (MI) versus non-infected individuals9. More than half of all HIV patients may have ECG abnormalities such as a prolonged QT interval, which can be associated with sudden death10.

Older HIV patients needing concomitant drugs for age-related conditions may have a higher risk of drug interactions with outcomes such as gastrointestinal intolerance, central nervous system disorders, liver toxicity, dyslipidemia, and loss of bone mass11.

Liver disease is also a major cause of death, and tuberculosis (TB) remains a leading cause of death among HIV-infected individuals in developing nations 11, 12. HIV infection has additionally been linked to a risk of insulin resistance with nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs) further increasing insulin resistance and the risk of diabetes10.

Finally, there has been a documented increase in cancers of the anus, liver, and lung, and in Hodgkin’s lymphoma since ART’s introduction in 1995. Zidovudine (azidothymidine) and the now discontinued zalcitabine (Hivid) have both been cited as contributing to the carcinogenic effects of ART. Other links have also been made between HIV and non-AIDS defining cancers specifically caused by infections such as Heliobacter pylori in gastric cancer, Chlamydia pneumoniae in lung cancer, and human papilloma virus (HPV) in cervical cancer 13.

Key Prognosticators of Mortality in Applicants with HIV and Risk Selection

Most insurance underwriting guidelines require that an HIV-infected applicant be currently under treatment with ART and can demonstrate adherence to treatment and follow-up for at least six months. Some insurers require a longer period of time to ensure appropriate compliance and medication effectiveness.

Key prognosticators to keep in mind are:

- Current Viral Load

Undetectable viral load is an absolute requirement, although consideration could be given if there is a history of viral “blips” – e.g., a transient viral load of up to 400 copies per milliliter which then normalizes quickly.

- Nadir CD4 Count

Most underwriting guidelines take a less than favourable view of covering HIV-positive individuals if a history exists of a CD4 + T-cell count of less than 200 cells/μL (AIDS, by definition) or of AIDS-defining clinical conditions (per the CDC), as this commonly means there has been significant damage to the immune system and irreversible damage to body systems. An exception to this might be an applicant with comorbid pulmonary TB that has been treated without sequelae.

It should be noted that CD4 counts continue to rise with ongoing ART therapy, thus the nadir CD4 count may be of less importance over time if CD4 recovery has been demonstrably stable. A recent paper demonstrated that after five years of ART, mortality outcomes of patients with low baseline CD4 counts converged with mortality of patients with intermediate and high baseline CD4 counts14.

- Current CD4 Count

A current (within six months of application) CD4 count of at least 350 cells/μL is

a minimum requirement for consideration of coverage. However, with new clinical treatment guidelines promoting the commencement of treatment to everyone worldwide with HIV regardless of CD4 count, best-case thresholds for those with CD4 counts greater than 500 cells/μL are now being seen.

While CD4 cell count at diagnosis can be highly predictive of mortality in the first year, this predictive value becomes no longer statistically significant three to four years after ART is initiated. An analysis of patient data from 15 of the 19 cohorts in the ART Cohort Collaboration study found that among 14,208 patients, CD4 cell counts and viral loads at the drug’s initiation were no longer prognostic of full-blown AIDS or of death after 36 months15. Another study, of 14,932 HIV patients in South Africa, found the effect of time on mortality was constant after 36 months on ART for all CD4 counts16.

- Comorbid Risk Factors and Disease

Significant comorbidities generally preclude coverage of HIV-infected individuals. Companies vary as to what qualifies as a “significant” comorbidity. For example, people co-infected with HIV and hepatitis viruses tend not to do well clinically. The medical literature also shows that HIV patients are developing and dying prematurely from vascular disease, so a more cautious view should be taken if the applicant also smokes, has diabetes, or has already developed cardiovascular disease.

There is a significant body of literature demonstrating very high mortality in HIV-infected individuals who are also intravenous drug abusers. Comorbid alcohol or drug abuse is a concern, although some underwriting latitude may be permissible for those using medically prescribed marijuana (depending on the indication). As there is also an increased suicide risk in HIV-infected individuals, insurers should also be concerned about any significant psychiatric history.

Determining Underwriting Ratings and Premiums

As with any impairment, there must be evidence to support any proposed extra premium being charged when an applicant has HIV. Care should be taken to be sure products for this block are fairly underwritten, priced and marketable, and will not damage company solvency.

Rating guidelines developed for covering HIV-positive individuals will depend on the following:

- Type of insurance product

- Term of coverage

- Selection criteria

- Insurable age: Few deaths are expected among very young people, thus it does not take many extra deaths in this cohort to make that group potentially uninsurable

- Smoking status: Even though an applicant with HIV might be assessed for smoker rates, additional loading may also need to be considered

These criteria and ratings will most likely vary by country, depending on availability of testing and access to affordable antiviral therapy and treating specialists.

Conclusion

The recent paradigm shift in the insurability of HIV has been a long-awaited event. Nevertheless, HIV remains a complex and potentially serious disease. Medical insurance directors will need to work closely with their companies’ actuarial, business development and marketing departments to ensure that insurance coverage is accurately assessed and priced and that consumer needs and expectations are addressed appropriately.

.png?sfvrsn=ab44a388_0)