Testosterone testing is on the rise in the U.S. and United Kingdom.1

Some of this rise is probably related to the increasing awareness of the symptoms of testosterone deficiency (TD) among males. These symptoms include fatigue, decreasing libido, depression, sleep disturbances, deceasing strength and possibly cognitive changes. Informal surveys suggest that these symptoms are very common as men age.2 ‘Direct-to-consumer’ advertising on television and other forms of media suggests that the detection and treatment of TD may restore masculine vitality to those men with symptoms of ‘low T’. Furthermore, specialty male hormone clinics cater to this ‘need’.

The symptoms of TD are very common in men, although many men with these same symptoms do not have TD. The actual incidence of low testosterone (levels < 300 ng/dL) in men above the age of 45 has been estimated to approach 40% of the population in a primary care setting.3 The incidence of TD is even higher in those who are obese and have Type 2 diabetes. It is important to consider the mortality implications of abnormal serum testosterone levels and the possible impact of exogenous testosterone therapy.

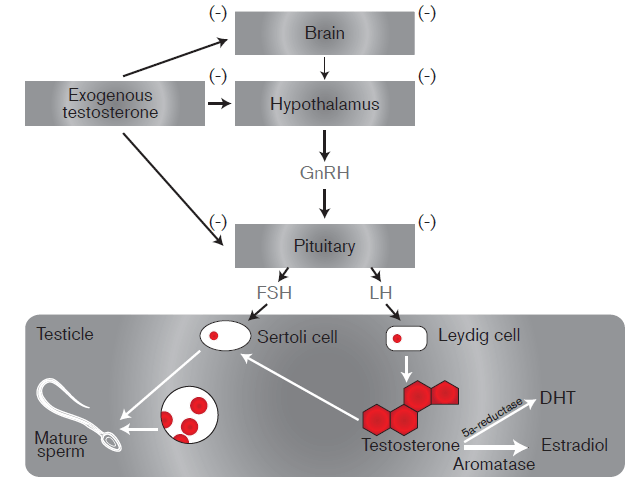

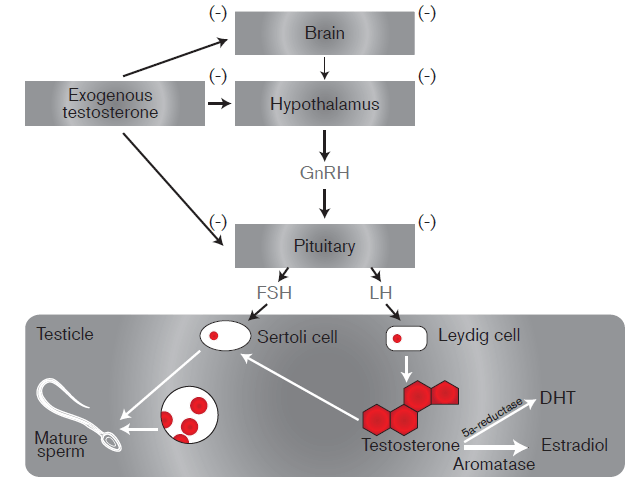

Testosterone is an anabolic hormone naturally produced in the testicles. It is responsible for the maintenance of muscle mass, plays a role in the production of red blood cells, and is necessary for the development of male sexual characteristics. It reduces fat mass and improves insulin sensitivity. In addition to the symptoms of TD noted in the previous paragraph, TD may cause a reduction in muscle mass (sarcopenia), increase body fat, decrease serum HDL cholesterol, decrease in hemoglobin, and lead to osteoporosis, and erectile dysfunction.

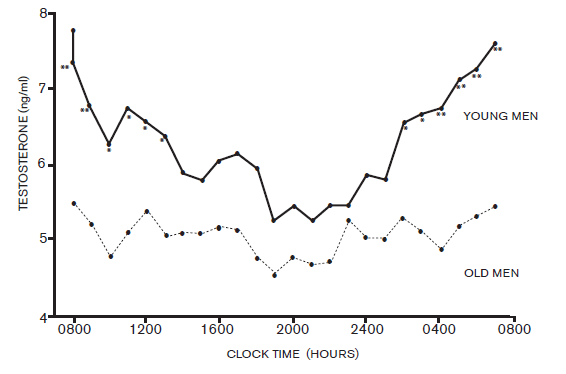

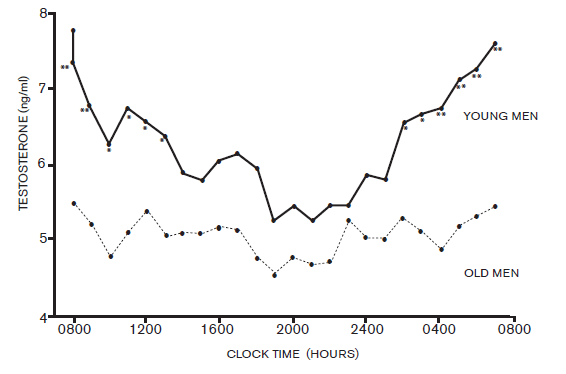

The level of testosterone normally varies throughout the day, with a peak reached at approximately 8 a.m. As men age, not only do the basal levels of testosterone gradually diminish, but the morning peak also gradually disappears. This decline is estimated to be as much as 2% per year.4

Measurement of serum testosterone is usually performed in the morning, in order to measure the peak levels of this hormone. Obesity can affect serum testosterone levels. It is not unusual to have low total serum testosterone levels in obese males, whereas the free serum testosterone levels in the same individuals can be in the normal range. It is therefore recommended that free testosterone should also be measured in obese men with low total testosterone.

Lower testosterone levels are associated with a higher risk of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality among men.5 This relationship also exists for dihydrotestosterone, a metabolite of testosterone, but not for estradiol, another metabolite of testosterone. Some studies show that, in older subjects, the optimal all cause survival is demonstrated in those people with mid-range levels of testosterone, suggesting that there may be a U-shaped relationship between testosterone levels and mortality.6

Testosterone therapy often results in increase in muscle mass and strength, as well as reduction in fat mass. Bone mineral density usually increases as well. The effect on erectile dysfunction is less clear. Testosterone administration also reduces insulin resistance and can improve the lipid profile. While these benefits are usually desirable, the balance between the risk and benefit of therapy is still being debated.7

The study submitted by Vigen et al. to JAMA in 2013 demonstrated that, among testosterone-deficient entrants from the Veterans Affairs medical centers, the hazard ratio for the combined outcome of MI stroke and overall mortality was 1.29 in the group that was given testosterone therapy vs. those who were not treated. The increased risk was present regardless of which testosterone preparation was used. This outcome certainly merits further study. It suggests that, while testosterone deficiency is related to additional mortality risk, simply treating the deficiency is not entirely beneficial, and may in itself entail considerable risk. It is this risk that is important for insurance medical directors and medical underwriters to fully appreciate. Its significance is compounded by the high prevalence of low testosterone levels among aging males, and the increasing prescription of testosterone replacement products.

While all-cause mortality is of paramount importance to life insurers, specific causes of increased mortality or morbidity risk can make a difference in assessment of specific cases. The primary complications of testosterone therapy are increased cardiovascular risk, worsening of sleep apnea and an increase in red blood cell counts (with possible polycythemia in some men). Other factors to consider are mild peripheral edema, prostatism (with elevations of PSA), hypogonadism, increased aggression and mood disorder, infertility, acne, and gynecomastia. The presence of gynecomastia is related to metabolites of testosterone that cause breast development, specifically estradiols. This is the reason that some men being treated with testosterone replacement therapy are also being treated with medications such as Arimidex (i.e., to block the estrogenic properties of the estradiols).

Although the primary cause of TD is related to aging and ‘andropause’, there are a number of other causes that should be mentioned. Two important causes for underwriters are obesity/diabetes and chronic alcoholism. Some of the other less prevalent causes are:

- Past hx of anabolic steroid abuse

- Disease or loss of testicles

- Chemotherapy or radiation therapy

- Medications (e.g.,drugs used to treat prostate cancer, corticosteroids)

- Genetic conditions such as Klinefelter’s Syndrome XXY

- Hemochromatosis

- Sarcoidosis

- Pituitary gland disease

- Chronic Illness

- Chronic kidney failure

- Liver cirrhosis

- Prolonged stress

Testosterone therapy can be administered in a variety of ways. Intramuscular injections can be given every 1 – 2 weeks. These rapidly elevate serum testosterone levels, but tend to lead to very high peak levels. Testosterone patches (e.g.,Androderm) require nightly application. Several different formulations in a cream or gel can be applied topically to the skin (e.g.,AndroGel, Testim and Fortesta). Gels are currently the most common method of testosterone administration. Other formulations include mucoadhesive preparations that are applied to the buccal mucosa and sublingual troches or lozenges. One of the newer preparations (Axiron) is a testosterone ‘stick’ applied to axillary skin. The last of the available options is a long acting subcutaneous implant, which needs to be renewed every six months.

At present, testosterone replacement therapy is contraindicated in males with a history of prostate cancer (since it can elevate PSA levels), as well as those with a history of breast cancer and severe obstructive uropathy.

The importance of testosterone replacement therapy for the insurance market has not yet been fully realized; however, the increasing use replacement therapy is likely to present challenges for underwriters. Testosterone deficiency in aging males is very common, but it is not entirely clear how replacement therapy will affect mortality outcome. While it is known that TD is associated with excess mortality, it is also suspected that supplementation will increase risk as well.

Current treatment guidelines suggest that testosterone supplementation should be initiated in patients with symptomatic, unequivocally low testosterone levels confirmed by repeated laboratory tests.8 Physicians are further discouraged from routine testosterone replacement therapy based on only one low testosterone level. This advice, however, is not always meticulously adhered to. Even the accepted range of low testosterone is not universally accepted. It ranges from 200 – 350 ng/dL. Additionally, this lower level of ‘normal’ is probably most relevant in younger, healthy males. A ‘normal’ lower limit in older men could be significantly lower.

Layton et al.1 have indicated that it is not only testosterone-deficient men who are being treated. It is not uncommon for men with normal serum testosterone to seek testing and to receive supplementation. His study showed that, in the U.S., between 4 – 9% of testosterone treatment is being given to men with normal or even high testosterone levels.

At times, supplementation may result in levels of serum testosterone far in excess of the upper limits of normal. Should this be considered a form of steroid abuse? If so, what underwriting action would be reasonable? Consideration is also necessary to determine whether supplementation raises the overall mortality risk to the point that Preferred mortality expectations are exceeded.