The weighty issue of self-reported BMI

RGA recently conducted two comprehensive studies to evaluate the accuracy of self-reported build information in insurance applications, and the results were eye-opening. In one study with typical life insurance applicants, self-reported BMI understated risk by up to 3.2% compared with various third-party evidence (Figure 1).

The other study with direct-to-consumer applicants showed mortality risk differences ranging from 5% to 9% compared to medical claims BMI.

Furthermore, research by ExamOne, a medical testing and diagnostics company, shows that 18.2% of US life insurance applicants fail to declare they are obese or morbidly obese.

This discrepancy isn't just a matter of vanity pounds; rather, it has significant implications for the insurance industry, as increases in BMI below 25 and beyond 29.9 correlate to elevated relative risk (Figure 2).

Underestimating BMI can lead to miscalculated risk and mispriced policies, potentially affecting the financial stability of insurance companies and premium fairness for all policyholders.

The power of third-party evidence

How can insurers secure a more accurate picture of applicants' health? The RGA studies suggest that third-party evidence sources hold a key. Attending physician statements (APS) and electronic health records (EHR) emerged as the closest alternatives to traditional paramedical exams, with BMI availability rates of 93% and 75%-79% respectively.

These sources not only provide more accurate data but also offer a more comprehensive view of an applicant's health. They can capture BMI changes over time and provide context that self-reported data often lacks.

The RGA studies revealed four key insights into the nature of BMI underreporting and how third-party evidence can counter them:

- Gender and age differences – Medical claims data showed slightly higher BMI availability for females and older individuals, likely due to their more frequent healthcare provider visits.

- Data recency – On average, BMI information within medical claims data was 1 to 2 years old, while LabPiQture BMI was 3 to 4 years old (Figure 3). This difference in recency may explain the varying effectiveness in detecting BMI under-reporting.

- Availability across sources – Aside from paramedical exams, which are considered the gold standard for current BMI measurement, APS had the highest BMI availability (93%), followed by EHR, with similar results between the two EHR vendors (75%-79%). When both medical claims and LabPiQture were available for the same individual, medical claims provided BMI data more frequently (28% vs. 13%).

- Direct-to-consumer channel – The studies found that BMI underreporting was particularly significant in the direct-to-consumer life insurance channel, highlighting a potential area for increased scrutiny.

The missing puzzle piece: Behavioral science

While third-party evidence is crucial, it is not the whole story. Enter behavioral science. Its goal is to help make sense of humans. It strives to address the differences between what people say they do and what they actually do.

RGA's behavioral science team has conducted randomized control trials involving more than 30,000 individuals from 10 markets to explore how the principles of behavioral science can improve disclosure rates in insurance applications. The team's research suggests three key principles for increasing the accuracy of applicant disclosures in general:

Applying these principles to BMI, two effective strategies emerge:

- Create an acceptable “normal” – Currently, most applications bluntly ask: “How much do you weigh?” This does nothing to make people comfortable disclosing higher weights. RGA behavioral science research found a better way to elicit more truthful responses.

By providing a sliding scale with a high but realistic end point, customers perceive higher weights to be more socially acceptable, reducing the stigma and prompting more accurate disclosure. This is called anchoring, and research shows it makes it easier to be truthful.

But what about making it easier to be accurate and harder to lie? RGA’s research found solutions there, as well.

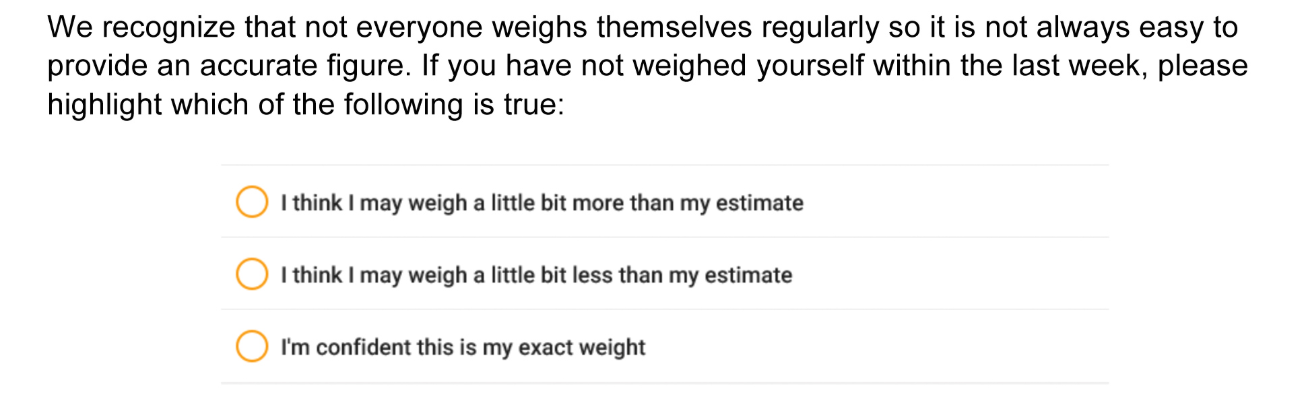

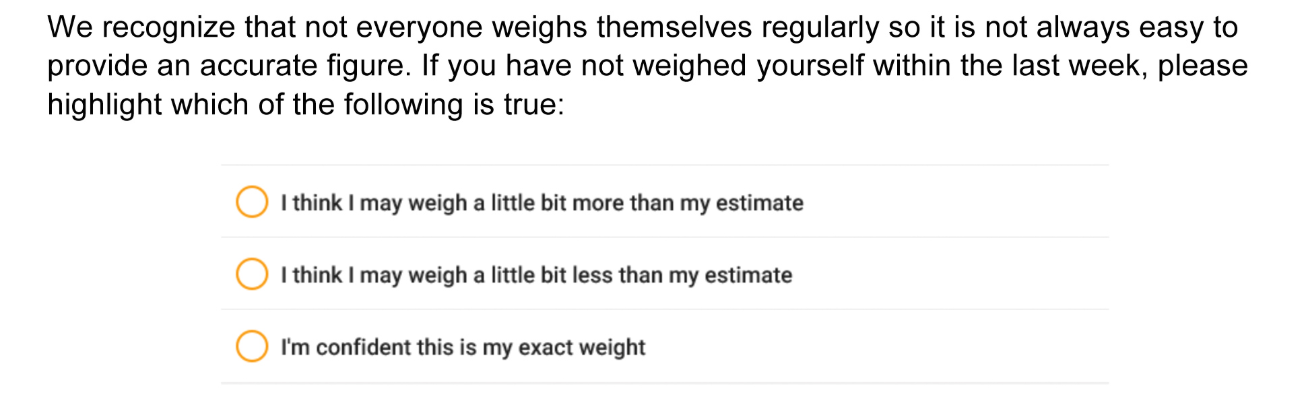

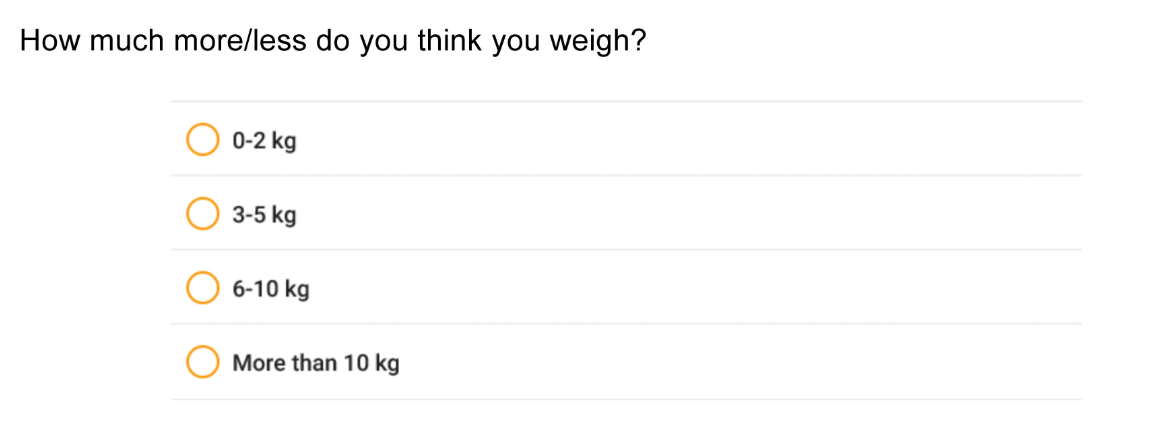

- Ask twice – Double-confirmation questions trigger the sentinel effect. This occurs when applicants rightly feel as if their responses are being checked for accuracy. Applicants often fail to disclose the truth because they believe the chances of their inaccuracy being discovered are small. However, asking the question a second time in a different way can make people feel that their responses may be scrutinized more closely than they initially thought. This makes it harder to lie. The first question can look like this:

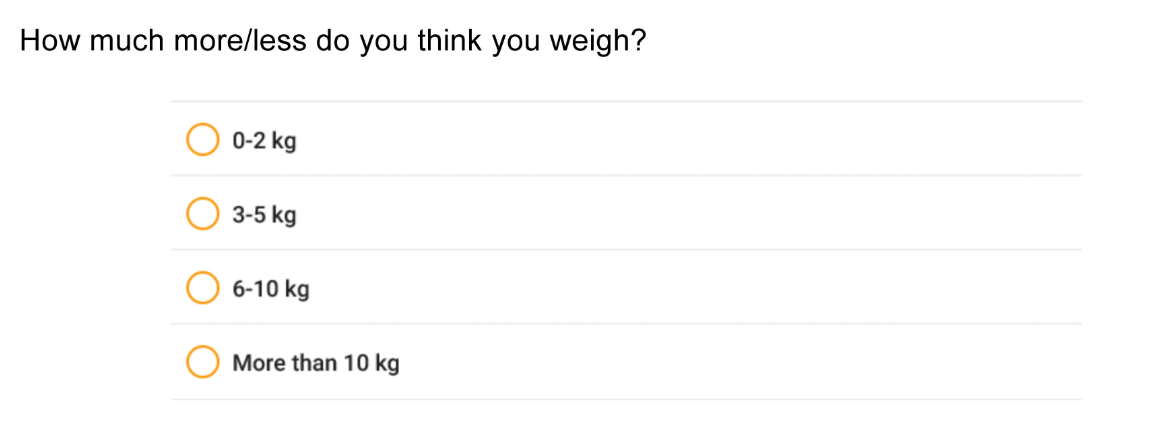

This empathetically framed question is immediately followed by a second question that goes beyond truth and speaks directly to accuracy:

When asked this way, 31% of respondents disclosed that they likely weigh more than the answer they had just given, and 16% indicated they likely weigh less. For those who acknowledged weighing more, the average estimate increased the BMI value by 1.2. Thus, this method makes it harder to lie and easier to be accurate.