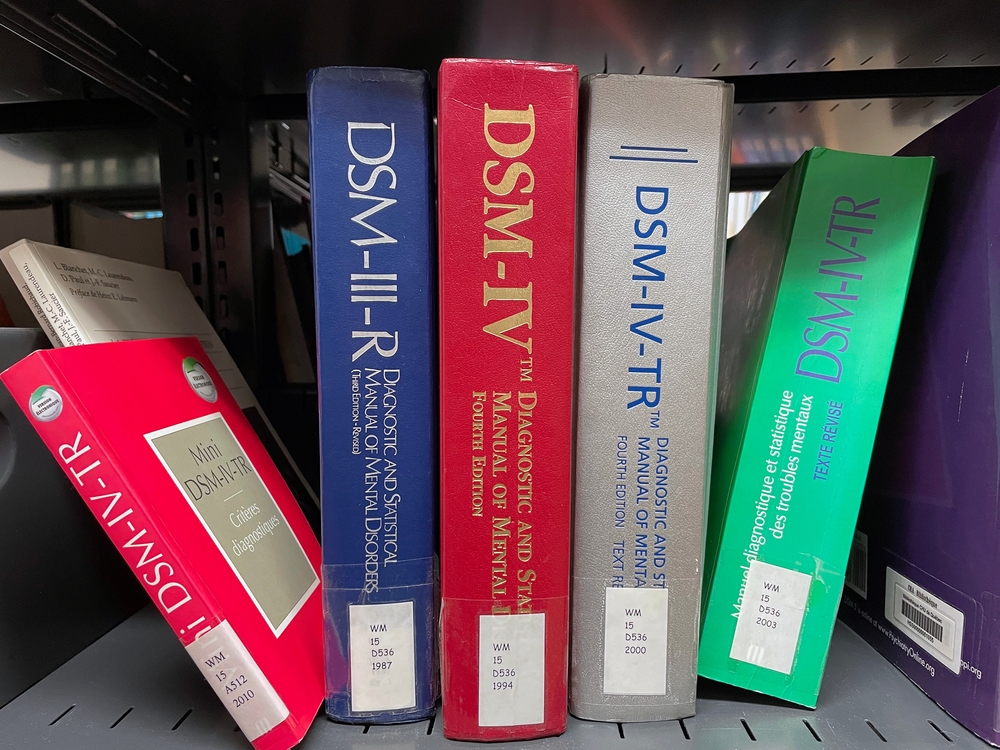

The publication in May 2013 of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders Fifth edition (DSM-5)1 engendered significant controversy over some of the changes from the fourth edition (DSM-IV)2.

Indeed, one editorialist recommended that DSM-5 be used either cautiously or not at all3. But a side-by-side review of both DSM-IV and DSM-5 does not show substantial changes or justify the fuss that has been raised. In this article, we will review many of the major changes that will be of interest in underwriting, comparing DSM-IV directly with DSM-5 and discuss what impact, if any, we can expect from these changes.

History

Efforts began as early as the 1840s to provide a standard classification for mental disorders4 in institutionalized individuals. By 1880, there were seven classifications: mania (agitation), melancholia (depression), monomania (psychosis), paresis, dementia, dipsomania (alcoholism) and epilepsy. The first DSM was published in 1952. Subsequent editions were revised and expanded and a multiaxial assessment system was added in 1980. DSM-IV was published in 1994. DSM-5 comprises nearly 1000 pages.

Purpose of DSM-5

The preface to DSM-5 states that the purpose of the publication, in addition to updating and streamlining diagnostic categories, is to harmonize these classifications with the upcoming International Classification of Diseases Eleventh edition (ICD-11) due to be released by the World Health Organization (WHO) in 2015. As a result, many of the changes are more organizational than substantive as will be discussed below. The multiaxial system of assessment has been eliminated and the Global Assessment of Function (GAF) has been replaced by the WHO’s Disability Assessment Schedule (WHODAS).

Major Changes in Diagnostic Categories

One of the most controversial changes is the removal of the so-called “bereavement exclusion”. In the DSM-IV criteria for Major Depressive Episode there is a caveat to consider if the symptoms were not better accounted for by bereavement within the previous two months, though this caveat did not specifically exclude a diagnosis of Major Depressive Episode. This caveat was eliminated in DSM-5 noting that, although symptoms may be attributed to a loss, the presence of a coexisting depressive disorder should also be considered. Substantial criteria are given in a footnote to help distinguish normal grief from a major depressive disorder. Critics say this will result in normal grief being “medicalized” and inappropriately treated with psychotropic drugs5, but when one places DSM-IV side-by-side with DSM-5 there are more-robust criteria for distinguishing between grief and depression in DSM-5. If the criteria are applied appropriately there should be no increase in bereaved people being diagnosed with major depressive episodes. If the criteria are not applied properly, it is not the fault of the criteria. Insofar as underwriting is concerned it is incumbent on us to understand these criteria so we classify the risk appropriately.

In DSM-IV, substance-related disorders including alcohol-related disorders were divided into abuse and dependence, with specific criteria for each. In DSM-5 these are combined as Substance Use Disorder. However, almost all of the DSM-IV criteria for both substance abuse and substance dependence are included in the DSM-5 criteria for Substance Use Disorder with minimal changes. It is unlikely, therefore, that any significant increase will occur in the diagnosis of these disorders and the impact on underwriting should be minimal.

Another change of interest to underwriting is in the Feeding and Eating disorders chapter. In DSM-5 under Bulimia there is no longer a distinction between purging and non-purging types as there was in DSM-IV. Underwriters should be aware of this change as the risk classification in these individuals may depend on this distinction. Also, a new diagnostic category is presented in this section: Binge-Eating Disorder, distinct from bulimia. This diagnostic category was a diagnosis for further study in DSM-IV and criteria include recurrent episodes at least weekly over three months of significant overeating with associated problems and distress, but without the inappropriate compensatory behaviors seen in bulimia.

Autistic disorder, Asperger’s disorder and the other pervasive developmental disorders are combined in DSM-5 under Autism Spectrum Disorder. Qualifiers for specific genetic disorders such as Rett syndrome are classified as Autism Spectrum Disorder with Rett syndrome. Since these criteria are reorganized rather than changed, once again there would not be any expected impact on diagnosis or underwriting.

The dementias are now classified under Major Cognitive Disorder. Again, specifiers of subtypes are used such as “Major Cognitive Disorder due to Alzheimer’s disease”. The criteria for these remain mostly the same as in DSM-IV; however, there is a new category of Minor Cognitive Disorder. Minor Cognitive Disorder is distinguished from Major by having “modest” as opposed to “significant” cognitive decline and does not involve impairments in the instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs). This addition is not groundbreaking; clinicians for some time have been using the term “mild cognitive impairment” to describe individuals with mild changes but not full-blown dementia. Despite this addition, the challenge for both clinicians and underwriters remains how to distinguish between normal aging and Minor Cognitive Disorder as we recognize that there is a continuum from minor to major cognitive disorders and mortality is significantly increased with the latter. This change is not likely to resolve this uncertainty, so therefore it is unlikely it will have much impact on the underwriting of this impairment.

Other Changes

Bipolar disorder is given its own chapter in DSM-5, but there are no significant changes in the criteria. The criteria for personality disorders are unchanged, but in section III of the manual an alternative model for understanding these problems is offered that focuses on personality function and differential diagnosis. Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is now separated from the anxiety disorders and included with the Adjustment Disorders in a new chapter called Trauma and Stress-Related Disorders. The criteria are reorganized but not substantially changed although additional diagnostic information for children aged six and under are added.

Other New Diagnostic Categories

Hoarding Disorder and Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder are new categories that are certainly familiar through the popular media; an ongoing television series focuses on individuals with the former. Illness Anxiety Disorder and Somatic Symptom Disorder are new categories, but actually cover what were previously categorized as hypochondriasis, somatization disorder and undifferentiated somatoform disorder in DSM-IV. Disruptive Mood Dysregulation Disorder describes individuals aged 6-18 years with severe temper outbursts grossly out of proportion to the situation occurring at least three times a week for 12 months, inconsistent to the developmental level of the individual and in multiple settings. Meeting all of these criteria should distinguish this disorder from an occasional temper tantrum.

Conclusion

While there are some changes in DSM-5, on close review and comparison with DSM-IV, the changes are not likely to have any substantial impact on underwriting or on practice and diagnosis. In summary, it is difficult to see what all the fuss is about. Diagnostic uncertainty is a part of all medicine, not just psychiatry as one observer noted6. Likewise in underwriting, certainty is unachievable but understanding and familiarity with the concepts of and criteria for these diagnoses enable us to make the best decisions possible regarding the risk classification of individuals with these problems.