Key takeaways

- Frailty is a complex, age-related condition that significantly increases vulnerability to adverse health outcomes in older adults, including higher risks of mortality, disability, and hospitalization.

- Early identification and intervention – especially through exercise, nutritional support, and medication review – can help prevent or slow the progression of frailty, improving quality of life and care planning for older adults.

- As the global population ages, recognizing and addressing frailty is crucial not only for individuals and healthcare systems but also for insurance, which must adapt to the growing needs and risks associated with an aging society.

The world’s population is projected to grow for another 50 to 60 years, reaching an estimated peak of about 10.3 billion by the mid-2080s. This represents a significant increase from the estimated 8.2 billion in 2024.

Population aging is a universal phenomenon, and this demographic shift will result in a substantial rise in the number of individuals aged 60 years and above. By 2030, it is expected that one in six people worldwide will be 60 or older, amounting to approximately 1.4 billion individuals. By 2050, this number is projected to increase to 2.1 billion, with the population of those aged 80 and above tripling to 426 million.1 As our population ages, we can also anticipate an increased prevalence of geriatric issues, such as frailty.

What is frailty?

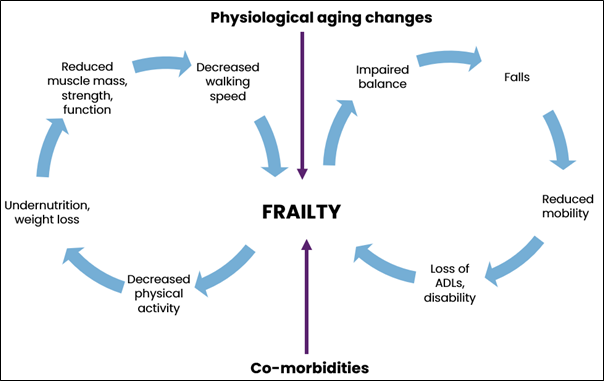

Frailty is a complex, multi-factorial, and age-associated clinical condition. It is characterized by a combination of various contributing factors that increase the likelihood of adverse health outcomes in older adults.2

As the proportion of older adults continues to rise, frailty is becoming an increasingly important health concern.

Research has shown that frailty is linked to elevated risks of mortality and morbidity. Individuals with severe frailty are generally considered uninsurable due to these elevated risks.

Pathophysiology

Frailty is caused by cumulative cellular damage from various sources throughout an individual's life. This damage leads to a gradual reduction in the homeostatic reserve of physiological systems. Despite this reduction, many older adults manage to maintain their functional abilities as they age. However, when stress or injury impacts these physiological reserves, it can result in decompensation and increased frailty.3 The evidence suggests that dysregulated stress response systems – including immune, endocrine, and energy response systems – play a crucial role in the development of physical or syndromic frailty.

A key physiologic component of frailty is sarcopenia, the age-related loss of skeletal muscle and muscle strength.4 The decline in skeletal muscle function and mass is often a consequence of age-related hormonal changes and alterations in inflammatory pathways, including an increase in inflammatory cytokines.5

Risk factors

Figure 2: Examples of risk factors for frailty7,8,9

Psychological factors such as anxiety, depression, and concerns about falling (CaF) have also been identified as possible risk factors.