Who was using the term "social distancing" six months ago? According to Google, the answer is virtually no one.

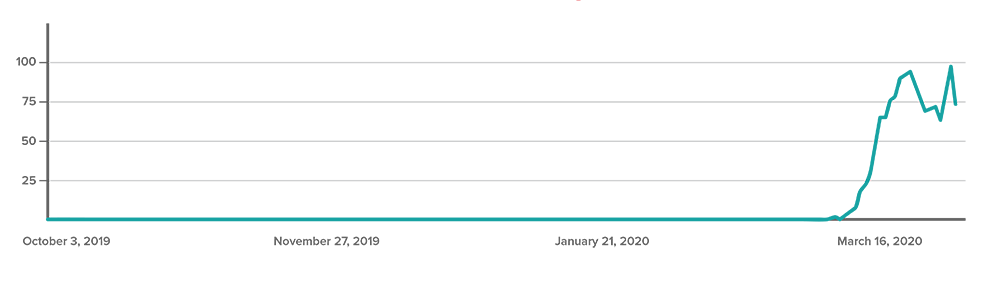

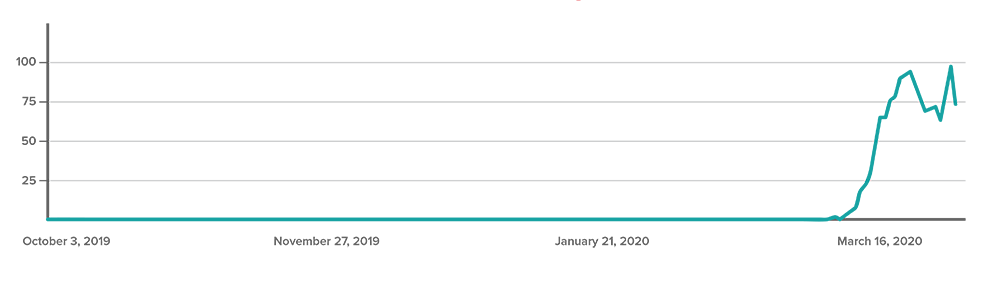

As this chart from Google Trends illustrates, until March 5, searches using this term were rare (see Figure 1). Then social distancing suddenly exploded into the public consciousness amid the spreading COVID-19 pandemic. Governments and global public health authorities embraced these two words to communicate a wealth of measures communities should be taking to reduce the rate of viral transmission and help manage a public health emergency.

Figure 1: Google Searches for "Social Distancing"

Source: Google Trends, data taken on April, 3 2020

Can it be right that, during one of the most important and comprehensive attempts to change behavior in recent history, authorities are asking the public to understand and act upon a new piece of jargon? Counterintuitive though it may seem, introducing a word or a phrase that demands explanation can actually encourage greater compliance. Insurers should take note.

Easy in, easy out

Criticism of the term social distancing stems from a simple premise: To encourage people to follow, instruction should be easy to comprehend. In this case, the argument goes, if we want people to adopt a certain behavior, the term for the desired conduct should already be widely understood.

There is ample behavioral evidence to support this point of view. Plenty of studies demonstrate that our opinions are influenced by how easily the brain processes information, a concept known as “processing fluency.” Human beings tend to prefer concepts that are simple to comprehend, and many find simple information more believable. Rhyming advertising slogans, an intuitive design, or a message using a common vernacular phrase have high processing fluency. Low fluency occurs when we find something difficult to interact with or understand.

Processing fluency is not uniformly positive. In fact, when information is “disfluent,” or more difficult to interpret, research suggests people tend to process it in a more considered way. This can lead to stronger recall. It’s possible that slightly jarring, complex, or novel messages could be more effective at getting us to pay attention, process, and remember certain arguments and instructions.

The psychologist Adam Alter, Associate Professor of Marketing at New York University's Stern School of Business, demonstrated this phenomenon in a series of famous experiments. In one study, his research team presented written information in two different typefaces – one difficult to read and one easy. Researchers then asked people to spot a typo in the text. The proportion who noticed the error in the hard-to-read font was higher than the easy-to-read alternative. Why? The harder-to-read font required the test subject to expend greater mental effort, prompting stronger information retention. Alter suggests that when something is difficult, this acts as cognitive alarm bell, or signal, to pay greater attention. In other words, easy in, easy out.

Having a simple, easy-to-process message is important when the behavior in question is simple and easy to understand. When the U.K. government sought to encourage Britons to avoid congregating to prevent the spread of disease, they used a simple tagline with high processing fluency: “Stay at home. Protect the NHS. Save lives.” Staying at home is a clear and easy-to-understand behavior.

But once an individual is outside the home, the multiple behaviors required, such as avoiding close contact with people, not visiting friends and family, avoiding public transport, and minimizing trips to supermarkets or physicians, can require a more complex series of choices. When something is new and needs a higher level of understanding, disfluency can be more effective in influencing behavioral change.

From BRICs to Brexit

New events or behaviors need new names to grab attention and signify their importance. Our attention is drawn to that which is novel and prominent. Amid information overload, this approach allows us to focus limited cognitive and attentional resources on key pieces of information.

Perhaps the most famous example of this phenomenon in recent years has been the coining of the term BREXIT. While “the U.K. exiting the European Union” is both a more accurate and easier to understand phrase, it fails to fully capture the enormity of the event and the change it entails. It did not matter that there was very little agreement over what BREXIT meant (see the claim from former U.K. Prime Minister Theresa May that ‘Brexit means Brexit’). The ambiguity in the term provided space to discuss its varied implications.

Taking a more global perspective, BRIC is one of the more influential new terms to have been created in recent years. Coined in 2001 by Jim O’Neill, then-chairman of Goldman Sachs Asset Management, BRIC is an acronym for Brazil, Russia, India, and China. In little over 10 years, the term came to define, not just a group of countries, but a new outlook on global economic and political power. As Gillian Tett wrote in an article for the Financial Times about the origins and influence of the BRIC label, it became “a near ubiquitous financial term, shaping how a generation of investors, financiers, and policymakers view the emerging markets.” The term BRIC may have needed some explanation at first, but now it has almost become shorthand. How many companies decided they needed a “BRIC strategy” because the label was created?

What exactly is social distancing, Dad?

The term social distancing has clearly entered the global consciousness and my own family's lexicon. My parents know it, my children know it. Did they fully understand it at first? No. But perhaps that is the point.

There have been countless newspaper articles written, radio phone-ins held, and TV pieces broadcast that have attempted to explain and discuss its meaning. The novelty of the term, combined with the importance of the issue, forces us to engage with important detail. A more common and everyday term might come with associations already attached that are not as relevant nor as useful. Some commentators have suggested authorities should use the term “physical” rather than “social,” as it is physical proximity that can spread disease and (virtual) social connection is important for mental and emotional support. This may be true, but it is hard to know if the phrase “physical distancing” would have sparked the same level of discussion and analysis needed to embed it into the public’s consciousness.

What seems undeniable is that the tide is turning, and simpler public health messages seem increasingly necessary to support key aspects of social distancing guidance. Around the world, supermarkets have placed signs on the floors of their stores to indicate the two-meter (six-foot) distance to be maintained when queueing, and many local councils and community authorities have taken steps to restrict access to playgrounds and communal areas and to mark safe distances in parks and public spaces. Nevertheless, data shows that journeys by car have started to rise in the U.K. again, suggesting that a direct message may be needed to deter people from returning to communal activities. Do we need a new term to help maintain behavior if the restrictions on movement continue for an extended period of time? Social distancing does not sound pleasurable, so will we need to focus on the positive aspects of this behavior. Rebranding may not be so difficult. The idea of not going abroad on vacation was cleverly reframed as a “staycation,” after all.

Like so much in this COVID-19 pandemic, we likely won’t fully understand why certain messages worked, and others didn’t, until well after this crisis ends. Even then, there may be no good counterfactual. What lessons can insurers take from this? Perhaps we can devote more thought to how we name new types of protection products and services, especially when such offerings provide coverage or convenience people didn’t know they wanted or needed. Consider final expense insurance, for example. Most people have not considered who will pay their often costly end-of-life medical and funeral expenses or how they will pay them. Why? They simply are not aware of the need. How could we label final expense insurance in an attention-grabbing way that inspires further investigation? What terminology can help move these products – and others – further into the general lexicon?

At the same time, like the supermarkets defining required distance between shoppers, we must be precise in our language in describing behaviors we want potential applicants to take.

The term social distancing likely will become part of the global lexicon for years to come. If it does, then it has done its job, and this may be important if we find ourselves facing similar challenges again.

.jpg?sfvrsn=182f3a99_0)